Tauba Auerbach

02 Sep - 04 Oct 2008

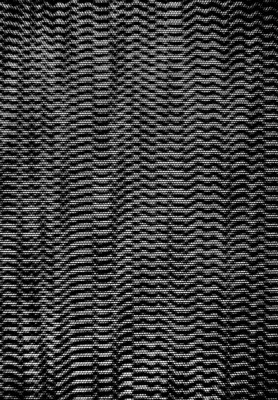

STATIC 6, 2008

Chromogenic print 60 x 42 in

Courtesy Jack Hanley, San Francisco, Deitch Projects, New York and Standard, Oslo

"The Exhibition Formerly Known as Passengers: 2.1"

Sept. 2–Oct. 4, 2008

Challenging the systems of language, Tauba Auerbach's artworks reconfigure letters to create word puzzles that lead the viewer to logical but unexpected conclusions. Auerbach has a background in typography and an interest in science. Her work is a complex exploration of semiotics, but it retains an essential visual accessibility and playfulness. She dissects language as a code of symbols and a conduit for ideas. Of particular interest to her is the anagram (a word or phrase formed by rearranging the letters of another), which historically has been utilized to carry secret messages or hidden meanings. Auerbach often bases her work on these sorts of solvable codes or systems. In one of her works, a series of reconfigured typewriters, she alters the keys so that their letters and symbols no longer correspond to what appears on the paper. The typewriters are painted with clues to the logic of their new operating systems; once each code is cracked, the machine becomes functional again.

This is Not an Alphabet

By Jens Hoffmann

For many decades artists have incorporated language, text, and words into their work in order to move away from pure pictorial representation and the fixation on art as an object. This use of language in art is firmly attached to 1960s Conceptualism, with artists such as Lawrence Weiner, John Baldessari, Bruce Nauman, Joseph Kosuth and the collaborative Art & Language using text as a way to shift towards artworks based on the study of language and its meaning in the context of visual art.

Today the use of text and language in the visual arts still holds a prominent position in the arsenal of contemporary artistic practices. We find artists that refer specifically to the first generation of Conceptual artists, for instance Jonathan Monk or Douglas Gordon, by creating text pieces that explicitly address this history; others such as Claire Fontaine or Ryan Gander understand the strong intellectual bent of Conceptual art as overly authoritarian and try to soften the grip of Conceptualism on contemporary art by ridiculing the idea of language as art. Yet others such as Liam Gillick are interested in systems of communication and work closely to the fields of graphic design and typography. Martin Creed's use of language is an ironic gesture inspired by a postmodern play on art history. And artists such as Cerith Wyn Evans or Glenn Ligon create their text works with a certain sense of nostalgia for a more political and far more radical era in art making.

Tauba Auerbach's work, however, sits outside any of the above-mentioned categories. More extreme and rigorous, her investigation of text, language, and letters goes straight to the heart of how our world communicates and explores the structure of language, the composition of words, phonology, syntax, and semantics.

While working in relationship to Conceptual art, Auerbach's practice revolves primarily around painting. She is a painter who paints letters. The meaning constructed from letters as visual signifiers fascinates the artist just as much as their shapes, forms, and ornamentation. Auerbach's meticulous examination into the origins of some of the most renowned typefaces also distinguishes her practice from other contemporary work incorporating typography.

With its particular 'non aesthetic' look, one of Auerbach's most well known paintings, How to Spell the Alphabet (2005), relates closely to early text pieces by Baldessari, that he employed sign painters to produce. This comparison is not necessarily a coincidence; Auerbach was trained and has worked as a sign painter. The omnipresence of murals, hand painted signs, and graffiti in the Mission district of San Francisco, Auerbach's home, and the strong craft tradition of the Bay Area, are other influences that give her work a uniqueness that is firmly rooted in a personal exploration of the relationship between content and form.

Following the Conceptual tradition of working with printed matter, Alphabetized Bible (2006) is an edition of eight books, each of which contains all the letters of the Bible in alphabetical order including punctuation. The text on the cover of these books reads 'Bbe ehHi llo Ty' made up from the words 'The Holy Bible,' and reminiscent of a word game, a doctor's eye-exam, a linguistics experiment, or perhaps visual poetry.

In recent years, the artist has moved away from her focus on typeface to explore the visual patterns created by alphabets and other systems of visual communication. She has used the Morse alphabet, sign language, and Braille on several occasions and is currently moving into more abstract territory. For her solo exhibition at the Wattis Institute, Auerbach presents two photographs, STATIC 6 and STATIC 7 (both 2008), depicting the visual remnant of static electricity captured on a television screen, as well as the painting Untitled (2008) that simulates a half-tone printing technique. This exhibition also includes Auerbach's first sculptural work, 50/50 XVII (2008), two resin forms that appear completely different from opposite angles. Extending her study of language into systems of logic, the new work in this exhibition explores how the mind creates order where there is none. By examining the phenomena of randomness and developing strategies for simulating uniformity, the artist continues her methodical examination of the organizing principles of language.