Perejaume

11 Apr - 20 May 2007

PEREJAUME

"Horizons and Waistlines Contrapàs"

A giant bird

Up on the mountain peak

Plays thecontrapàs with its tail

And sardanes with its beak.

(Popular song from Olot)

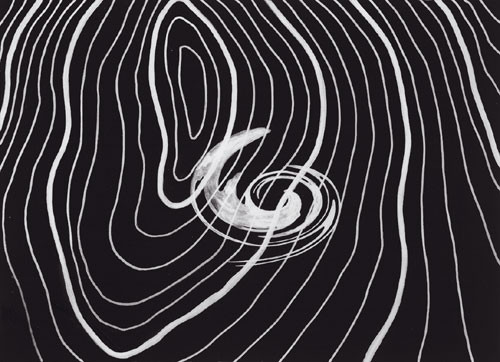

Dance is a natural instinct. All the peaks of the Earth appear measured. Observed in their succession, all the peaks of the Earth rise and fall like the sway of the sea swell. Hills and valleys form a perfect melodic unity that takes part motionless, or almost, in a dance that is so slow, so overstretched in time and space that no human folklore can record it. Yet mountains dance; the poses and undulations of terrain express all forms of dance. Through the varied development of their movements, in a turn that matches the curvature of the planet, with broken steps and consecutive steps, mountains revolve, winnow and cause ripples in their flanks. One fold in the terrain leads to another. Forming a circle or a row, mountains gather together and separate into countless figures, which reveal in which direction they move. For mountains curve and enliven their own style in the very rhythmic current that drags them along. As if when the air of the dance moving the mountains is stirred, their winnowing were intensified.

Mountains certainly move the wind. With a prodigality of widths and frequencies that cannot be checked, mountains move and blow the wind and the wind moves and blows the waves. As if it were time to flee, the windswept flourish of the water creates an oscillation of successive undulating, polymetric peaks on the surface of the sea. Sometimes in high relief, at other times with that billowy grace, full of folds that poets have called “petals”, “finger marks”, “beams” or “white horses”. All such topographical descriptions are, of course, only seemingly free. There is a set of dances that the waters obey as precisely as the firmest andmost ceremonious mountains of earth are able to. However, they do so with a much greater succession of shapes to the same extent to which the sea continuously folds its fabric, softening it, turning it over, rolling it and making it new again.

As regards large mineral folds, we come across hills and valleys that are draped, pressed, pleated or else have looped fabric. Folds, double folds and counter-folds that flare up before being cast down and collapsing roughly, raising their heads continuously until the earth descends into waves of fabric that stretch out over the first flat levels of the plain. This proves how the pounding of the hills on the plains regains a sea shape that is coastal, an undulation that breaks on the sand.

Let’s remain on a peak skirted with folds of fabric and watercourses, between valleys that move away and a sound of water falling in a cascade down the deepest folds in the flanks. We observe the lap of curves: the vegetation accumulated in certain folds and the fleecy skirted forests below. And lower still, the patterned flowery earth that acquires bell shapes in an interwoven blend of cereal and urban costumes. Needless to say, amidst these mountains we come across peaks that fall well beside others that are crumpled, springs of clay and stones with no apparent traditional dance influence. And yet this is but an outward appearance, for both are totalities of earth in action, totalities of paced earth governed by rhythm, of danced earth that is consequently filled with majestic movement.

It is difficult to express thismovement in a way that differs from how the territory itself does. Thanks to their compact flow, mountains experience and move the world: they indiscriminately skirt it and dance it, with the whole body of the Earth. It is difficult for us to imagine the extraordinary extension of the dance, with all the mountainous peaks considered as one single organism, with the countless stream beds and crest lines where inclines fold, where gradients are measured, as the only earth given to mountains in this world has previously been taken fromothers.Without being too sure whether that earthly mountain range is an exhibition of soil in infinite heaps, with infinite gaps, in order that it may be contemplated in a greater and varied surface. Or, on the contrary, whether themountain range is precisely the result of a remainder of this surface, an excess of form that should be folded, pleated, creased to fit into the world.

When we think of the world and of the wealth of its phenomena, we immediately think of the following danced expression made by hills and valleys, with the geological slowness of steps, with a scarcely animated yet constant choreography that folds up, consuming altitude, before diversifying fabrics, shapes and patterns even further. A whole unstoppable turn with conglomerates, clays, rising and falling of earth, with granite that despite seeming a dry rock is a flexible crust that produces gravel and sand... We can still trace the muscular efforts entailed in folds and the wealth of erosive agents, the scarification, shedding and hillocks between large damaged crumples of material. However imperceptible it may appear, this setting in motion is verifiable everywhere. Not in vain are there Amerindian tongues in which the word “mountain” is a verb of movement and, consequently, a delicate choreography of formand action. If in the midst of all this a mountain becomes unique this is due to the beauty of its chosen movements as it folds up and allows itself to be taken over.

“Anticlines and valleys, mounts, mountains and cols / I now see dressed in sleet and snow.” This is the first verse of a poem by Andreu Febrer, all the stanzas of which end in “ungla” (unguis). Snow has always had this double characteristic of protection and divestment. In Lo cornamusaire, one of his most important last poems, Jacint Verdaguer, aged and discouraged, personified the mountain in his own body, as he had done throughout his life, although this time the divestment is very acute and final: “Mountains, whitened today by a filament of ice, await in fear the snow of the approaching winter”. Snow, therefore, enfolds and exceeds, builds up and shrouds. Leaving aside swaddling clothes and shrouds, mountain ranges in their gleaming dresses remind us of the draped hills and valleys of classical sculpture, only visible through the materials and clothing that conceal them and only legible in the shadowy strokes of the shapes of the folds. In high and low reliefs, in sizeable and very extensive friezes, the perennial snows fold and unfold the peaks just as the stone drapery mineralises the respective movements in the sculptural images of dancers and warriors. In certain mountains the forest fabric produces a similar effect to this marbled fold of tunics. Dressed in coarsely woven dark clothes, forests round off slopes; aired and branchy, they flank them so unconstrainedly sometimes, so thinly luxuriant, that they appear loose-fitting expressly to encourage folds. Even toponymy can help us reaffirm this orographic application of wooded hillside –as in the case of the name of the Grimola hill, in the Montnegre holm-oak suntrap, which according to Joan Coromines derives from the depression below, from where the name extended, as is often the case, to the mountain above. The linguist believes, therefore, that “Grimola” was the name of the depression because gremiola (small laps) is the plural diminutive of gremium(lap).

Human beings have tried to de-petrify the folds through song, to make them tender, mellow, to soften them. The ploughing is continuous so that the human word may penetrate the dry rigidity; just as the strategies to make the earth dance, to ensure that the hills and valleys yield to our pace and our style are continuous, thereby managing to form a more harmonious part of the same territorial structure –as if the structure were still ductile or at least transferable to certain partners who ask her to dance. This is the myth of a leeward land, governed by song, climbed in voice and in steps, extolled in voice and in steps to the high point of the song. A land set to music with peaks and depressions in harmonious alternation, with dancers sheltered by the mountains, concealed in the mountains, with branches and channels filled with bells under full skirts with several laps, all of them lined with level curves.

Indeed, the yearning of the song consists in making the earth revolve, in the agrarian sense of turning it over, ploughing it, making it dance, elevating it with the most genuine of forms and the most diverse modalities of words, gestures and sounds, like a worldly luxuriance rising out of the world. For the mountain and the plain are distinguished from one another precisely for being a land sung and a land told.

This could explain why it is so easy for us to portray real horizons like measured ridges, and we find it equally suggestive to accept a sound correspondence for the formal vibration of the horizons. As if a certain incline were an inflection of the voice or the tune and the ridges were volumetric spectrograms, with sharp peaks and obtuse ravines, where each knoll in the mountain range matches a change of tune. All in a vast modulation of ridges. Upon my honour that we should not be surprised if this land that has been sung, this land that has been pronounced as if the very geological nature of sonority were expressed by it, should yield to the majestic undulation of horizons. For horizons dance, extremely slowly perhaps, but they do dance. If it were not for the dance, horizons would ferment in their permanence, putrefying in their lines. And this is how it must have always been, as the land itself seems to sing in the song from Riells del Montseny: “Weary, I’m weary, / Weary of dance steps. / Weary, I’m weary, / Until the world draws to an end.” Air, water and earth are one and the same surrendered rhythm. We return to the sea, which is where this condemnation to continuously turn horizons over becomes brighter, more attractive, as if the same movement carried us and the mountain away, climbing and descending the water in a sustained and continued alternation. As if the sea were pleated with the horizons folded inside the water, so that they emerge again. Save for the days of heavy sea, on which the water moves forward in great strides, all that blueness of mountain ranges with hills and hills becoming blurred grant the terrain an extremely rich rhythmic variety. Mountains with a film of light, bushy with light, quivering with light. In fact, the graceful flourish, the oscillating steps of the water, the plucking, and the intercalations greatly resemble the forward and backward movements made by dancers in the contrapàs. For the sea always moves until it stays as it was, as if there were a wind that blows and a wind that blows away. Just as in the contrapàs, according to Aureli Capmany, “The dancers, lined up and directed by the leader, must go around the square, measuring their steps with such precision that when the music is over they find themselves exactly in the place they started from”. This explains why sometimes the sea, in its whimsical swaying, seems to erect only one mountain rather than an endless string – one single mountain, fluid and oceanic; one single mountain on all sides, multiple, tremulous, repeated, ceaseless; a mountain that lives on, suspended, without definitively caving in on any beach or completely dying in any depth.

Human beings are only accustomed to facing the world with flailing arms or attempting to embrace the world swimming vigorously amidst this swell of mountain ranges. Those who have done so are well aware, however, that the world eludes us in the attempt and that we cannot reach it with our arms, have it, retain it and even less make it ours. The water meanders, swims against us and slips away. The tighter our grip, the more it slips away. Should the occasion arise, there is the possibility (much more passive) of letting oneself go and pretending to be dead on the water in order to perceive in one’s body the universal rocking, to surrender one’s body to the universal rhythmic and oscillatory evolutions that draw the water, the wind and the coasts. To allow oneself, stretched out on the water, to rise and fall caressed by that cadence, that softness and depth of the peaks, is a sincerely geographical act. We shall never know whether the water, the wind and the coasts are tackling a persistent and interminable undertaking, or whether they are dancing for the sake of dancing.

Finally, there is a contemporary form of territorial dance, a truly human movement of lands and materials toing and froing, mounts and levellings and truckloads in a great excavation, a great demolition, a great elevation and transfer of measurements and terrains. The hills in progress are another expression of this land today, that never stops moving because it is earth unearthed that rises up and runs along terra firma and is turned over, the continuous mobility of which is almost marine. A land exceedingly chewed, amassed and roused, transformed into a living body and a mooring buoy of beings and shapes, ground and re-ground, turning and spinning in a great nervous dance. A short shallow breath, followed by dislodged earth, earth that wanders around the Earth: ground that is no longer firm, condemned to roam about like men, condemned to doubt like men. For up until a few decades ago, the earth had a certainty about it that it has now lost and we sometimes see places where the earth seems worried, amidst provisional landscapes and materials that must be continously relocated, transitory, spoilt, withered after having been transplanted so many times.

In effect, we sometimes have the impression that we are inhabiting a vagrant land. A land where we have accelerated geologic time until we have made it human. A land that is in a hurry and that, unsteady as if the hills had exchanged their slopes, wallows on the limits of its own insecurity. As if the earth had swallowed men’s writing, as if the earth itself were writing that soared and plummeted. As if writing had assumed a three-dimensional dimension to reach us. As if right now these lines were to become a sort of place, and the place broke into some dance steps and began to turn with the folds arranged by the rhythm. Until all the earth of the place formed a sign with which to secure the various twists and turns of the text, towards the song, towards the mountain and the wave. So in the event that you found these very words to be uphill going, I think there can be no cross more appropriate for this earth-signmountain- movement than the one erected by Josep Maria Jujol on the Tower of the Cross in Sant Joan Despí. No landmark, in effect, is more apropos for a mountainmovement than Jujol’s windy cross, that iron cross, wide and sailing, that is a fixed image, forged into movement.

With palm, reed, hemp and rockrose material, with tulles and gauzes of mist and frost, with sparkles of water and draped undulations, the land flows and surges in the thickest of fabrics, with the most excellent and refined dyes. Needless to say there is a pictorial resolution in this form of mountainous dance, as pervasive as a sound vibration with the sky sitting astride of the peaks. It is a found painting, a flowing painting, with such density and substance that it takes to the mountains on its own; a painting woven with texts and steps in which we are matted and share the choreography with the whole world. There is nothing else, either within or without. So, spin around –skirts, overskirts and shirtwaisters falling loosely in countless folds, with undulating level curves beneath windswept crosses!

As Perejaume himself states, his writings –constructed with some of the voices “that offer greater resistance to literal translation” and that “enhance all that which is especially untranslatable”– are almost of the same nature as his work as a plastic artist, i.e., unique and untransferable. Like colours or sounds rather than containers of meaning, the voices in his texts strengthen “the euphonic secret” towards which the author guesses that language itself leads him. Writing, like horizon lines –oscillograms– is at once a pentagram and a vibrating chord.

The author wonders whether his writing is not a rejection “of the excessively communicational use of words, of the misuse that is often made of replacement and exchange, as if words could be copied out from one language to another totally and absolutely, without having anything quite their own.” By echoing this reflection we would like to draw attention to the difficulty entailed in rendering an essay such as Horizons and Waistlines in another language, well aware of both the value and the shortcomings of the art of translation. JosephineWatson

"Horizons and Waistlines Contrapàs"

A giant bird

Up on the mountain peak

Plays thecontrapàs with its tail

And sardanes with its beak.

(Popular song from Olot)

Dance is a natural instinct. All the peaks of the Earth appear measured. Observed in their succession, all the peaks of the Earth rise and fall like the sway of the sea swell. Hills and valleys form a perfect melodic unity that takes part motionless, or almost, in a dance that is so slow, so overstretched in time and space that no human folklore can record it. Yet mountains dance; the poses and undulations of terrain express all forms of dance. Through the varied development of their movements, in a turn that matches the curvature of the planet, with broken steps and consecutive steps, mountains revolve, winnow and cause ripples in their flanks. One fold in the terrain leads to another. Forming a circle or a row, mountains gather together and separate into countless figures, which reveal in which direction they move. For mountains curve and enliven their own style in the very rhythmic current that drags them along. As if when the air of the dance moving the mountains is stirred, their winnowing were intensified.

Mountains certainly move the wind. With a prodigality of widths and frequencies that cannot be checked, mountains move and blow the wind and the wind moves and blows the waves. As if it were time to flee, the windswept flourish of the water creates an oscillation of successive undulating, polymetric peaks on the surface of the sea. Sometimes in high relief, at other times with that billowy grace, full of folds that poets have called “petals”, “finger marks”, “beams” or “white horses”. All such topographical descriptions are, of course, only seemingly free. There is a set of dances that the waters obey as precisely as the firmest andmost ceremonious mountains of earth are able to. However, they do so with a much greater succession of shapes to the same extent to which the sea continuously folds its fabric, softening it, turning it over, rolling it and making it new again.

As regards large mineral folds, we come across hills and valleys that are draped, pressed, pleated or else have looped fabric. Folds, double folds and counter-folds that flare up before being cast down and collapsing roughly, raising their heads continuously until the earth descends into waves of fabric that stretch out over the first flat levels of the plain. This proves how the pounding of the hills on the plains regains a sea shape that is coastal, an undulation that breaks on the sand.

Let’s remain on a peak skirted with folds of fabric and watercourses, between valleys that move away and a sound of water falling in a cascade down the deepest folds in the flanks. We observe the lap of curves: the vegetation accumulated in certain folds and the fleecy skirted forests below. And lower still, the patterned flowery earth that acquires bell shapes in an interwoven blend of cereal and urban costumes. Needless to say, amidst these mountains we come across peaks that fall well beside others that are crumpled, springs of clay and stones with no apparent traditional dance influence. And yet this is but an outward appearance, for both are totalities of earth in action, totalities of paced earth governed by rhythm, of danced earth that is consequently filled with majestic movement.

It is difficult to express thismovement in a way that differs from how the territory itself does. Thanks to their compact flow, mountains experience and move the world: they indiscriminately skirt it and dance it, with the whole body of the Earth. It is difficult for us to imagine the extraordinary extension of the dance, with all the mountainous peaks considered as one single organism, with the countless stream beds and crest lines where inclines fold, where gradients are measured, as the only earth given to mountains in this world has previously been taken fromothers.Without being too sure whether that earthly mountain range is an exhibition of soil in infinite heaps, with infinite gaps, in order that it may be contemplated in a greater and varied surface. Or, on the contrary, whether themountain range is precisely the result of a remainder of this surface, an excess of form that should be folded, pleated, creased to fit into the world.

When we think of the world and of the wealth of its phenomena, we immediately think of the following danced expression made by hills and valleys, with the geological slowness of steps, with a scarcely animated yet constant choreography that folds up, consuming altitude, before diversifying fabrics, shapes and patterns even further. A whole unstoppable turn with conglomerates, clays, rising and falling of earth, with granite that despite seeming a dry rock is a flexible crust that produces gravel and sand... We can still trace the muscular efforts entailed in folds and the wealth of erosive agents, the scarification, shedding and hillocks between large damaged crumples of material. However imperceptible it may appear, this setting in motion is verifiable everywhere. Not in vain are there Amerindian tongues in which the word “mountain” is a verb of movement and, consequently, a delicate choreography of formand action. If in the midst of all this a mountain becomes unique this is due to the beauty of its chosen movements as it folds up and allows itself to be taken over.

“Anticlines and valleys, mounts, mountains and cols / I now see dressed in sleet and snow.” This is the first verse of a poem by Andreu Febrer, all the stanzas of which end in “ungla” (unguis). Snow has always had this double characteristic of protection and divestment. In Lo cornamusaire, one of his most important last poems, Jacint Verdaguer, aged and discouraged, personified the mountain in his own body, as he had done throughout his life, although this time the divestment is very acute and final: “Mountains, whitened today by a filament of ice, await in fear the snow of the approaching winter”. Snow, therefore, enfolds and exceeds, builds up and shrouds. Leaving aside swaddling clothes and shrouds, mountain ranges in their gleaming dresses remind us of the draped hills and valleys of classical sculpture, only visible through the materials and clothing that conceal them and only legible in the shadowy strokes of the shapes of the folds. In high and low reliefs, in sizeable and very extensive friezes, the perennial snows fold and unfold the peaks just as the stone drapery mineralises the respective movements in the sculptural images of dancers and warriors. In certain mountains the forest fabric produces a similar effect to this marbled fold of tunics. Dressed in coarsely woven dark clothes, forests round off slopes; aired and branchy, they flank them so unconstrainedly sometimes, so thinly luxuriant, that they appear loose-fitting expressly to encourage folds. Even toponymy can help us reaffirm this orographic application of wooded hillside –as in the case of the name of the Grimola hill, in the Montnegre holm-oak suntrap, which according to Joan Coromines derives from the depression below, from where the name extended, as is often the case, to the mountain above. The linguist believes, therefore, that “Grimola” was the name of the depression because gremiola (small laps) is the plural diminutive of gremium(lap).

Human beings have tried to de-petrify the folds through song, to make them tender, mellow, to soften them. The ploughing is continuous so that the human word may penetrate the dry rigidity; just as the strategies to make the earth dance, to ensure that the hills and valleys yield to our pace and our style are continuous, thereby managing to form a more harmonious part of the same territorial structure –as if the structure were still ductile or at least transferable to certain partners who ask her to dance. This is the myth of a leeward land, governed by song, climbed in voice and in steps, extolled in voice and in steps to the high point of the song. A land set to music with peaks and depressions in harmonious alternation, with dancers sheltered by the mountains, concealed in the mountains, with branches and channels filled with bells under full skirts with several laps, all of them lined with level curves.

Indeed, the yearning of the song consists in making the earth revolve, in the agrarian sense of turning it over, ploughing it, making it dance, elevating it with the most genuine of forms and the most diverse modalities of words, gestures and sounds, like a worldly luxuriance rising out of the world. For the mountain and the plain are distinguished from one another precisely for being a land sung and a land told.

This could explain why it is so easy for us to portray real horizons like measured ridges, and we find it equally suggestive to accept a sound correspondence for the formal vibration of the horizons. As if a certain incline were an inflection of the voice or the tune and the ridges were volumetric spectrograms, with sharp peaks and obtuse ravines, where each knoll in the mountain range matches a change of tune. All in a vast modulation of ridges. Upon my honour that we should not be surprised if this land that has been sung, this land that has been pronounced as if the very geological nature of sonority were expressed by it, should yield to the majestic undulation of horizons. For horizons dance, extremely slowly perhaps, but they do dance. If it were not for the dance, horizons would ferment in their permanence, putrefying in their lines. And this is how it must have always been, as the land itself seems to sing in the song from Riells del Montseny: “Weary, I’m weary, / Weary of dance steps. / Weary, I’m weary, / Until the world draws to an end.” Air, water and earth are one and the same surrendered rhythm. We return to the sea, which is where this condemnation to continuously turn horizons over becomes brighter, more attractive, as if the same movement carried us and the mountain away, climbing and descending the water in a sustained and continued alternation. As if the sea were pleated with the horizons folded inside the water, so that they emerge again. Save for the days of heavy sea, on which the water moves forward in great strides, all that blueness of mountain ranges with hills and hills becoming blurred grant the terrain an extremely rich rhythmic variety. Mountains with a film of light, bushy with light, quivering with light. In fact, the graceful flourish, the oscillating steps of the water, the plucking, and the intercalations greatly resemble the forward and backward movements made by dancers in the contrapàs. For the sea always moves until it stays as it was, as if there were a wind that blows and a wind that blows away. Just as in the contrapàs, according to Aureli Capmany, “The dancers, lined up and directed by the leader, must go around the square, measuring their steps with such precision that when the music is over they find themselves exactly in the place they started from”. This explains why sometimes the sea, in its whimsical swaying, seems to erect only one mountain rather than an endless string – one single mountain, fluid and oceanic; one single mountain on all sides, multiple, tremulous, repeated, ceaseless; a mountain that lives on, suspended, without definitively caving in on any beach or completely dying in any depth.

Human beings are only accustomed to facing the world with flailing arms or attempting to embrace the world swimming vigorously amidst this swell of mountain ranges. Those who have done so are well aware, however, that the world eludes us in the attempt and that we cannot reach it with our arms, have it, retain it and even less make it ours. The water meanders, swims against us and slips away. The tighter our grip, the more it slips away. Should the occasion arise, there is the possibility (much more passive) of letting oneself go and pretending to be dead on the water in order to perceive in one’s body the universal rocking, to surrender one’s body to the universal rhythmic and oscillatory evolutions that draw the water, the wind and the coasts. To allow oneself, stretched out on the water, to rise and fall caressed by that cadence, that softness and depth of the peaks, is a sincerely geographical act. We shall never know whether the water, the wind and the coasts are tackling a persistent and interminable undertaking, or whether they are dancing for the sake of dancing.

Finally, there is a contemporary form of territorial dance, a truly human movement of lands and materials toing and froing, mounts and levellings and truckloads in a great excavation, a great demolition, a great elevation and transfer of measurements and terrains. The hills in progress are another expression of this land today, that never stops moving because it is earth unearthed that rises up and runs along terra firma and is turned over, the continuous mobility of which is almost marine. A land exceedingly chewed, amassed and roused, transformed into a living body and a mooring buoy of beings and shapes, ground and re-ground, turning and spinning in a great nervous dance. A short shallow breath, followed by dislodged earth, earth that wanders around the Earth: ground that is no longer firm, condemned to roam about like men, condemned to doubt like men. For up until a few decades ago, the earth had a certainty about it that it has now lost and we sometimes see places where the earth seems worried, amidst provisional landscapes and materials that must be continously relocated, transitory, spoilt, withered after having been transplanted so many times.

In effect, we sometimes have the impression that we are inhabiting a vagrant land. A land where we have accelerated geologic time until we have made it human. A land that is in a hurry and that, unsteady as if the hills had exchanged their slopes, wallows on the limits of its own insecurity. As if the earth had swallowed men’s writing, as if the earth itself were writing that soared and plummeted. As if writing had assumed a three-dimensional dimension to reach us. As if right now these lines were to become a sort of place, and the place broke into some dance steps and began to turn with the folds arranged by the rhythm. Until all the earth of the place formed a sign with which to secure the various twists and turns of the text, towards the song, towards the mountain and the wave. So in the event that you found these very words to be uphill going, I think there can be no cross more appropriate for this earth-signmountain- movement than the one erected by Josep Maria Jujol on the Tower of the Cross in Sant Joan Despí. No landmark, in effect, is more apropos for a mountainmovement than Jujol’s windy cross, that iron cross, wide and sailing, that is a fixed image, forged into movement.

With palm, reed, hemp and rockrose material, with tulles and gauzes of mist and frost, with sparkles of water and draped undulations, the land flows and surges in the thickest of fabrics, with the most excellent and refined dyes. Needless to say there is a pictorial resolution in this form of mountainous dance, as pervasive as a sound vibration with the sky sitting astride of the peaks. It is a found painting, a flowing painting, with such density and substance that it takes to the mountains on its own; a painting woven with texts and steps in which we are matted and share the choreography with the whole world. There is nothing else, either within or without. So, spin around –skirts, overskirts and shirtwaisters falling loosely in countless folds, with undulating level curves beneath windswept crosses!

As Perejaume himself states, his writings –constructed with some of the voices “that offer greater resistance to literal translation” and that “enhance all that which is especially untranslatable”– are almost of the same nature as his work as a plastic artist, i.e., unique and untransferable. Like colours or sounds rather than containers of meaning, the voices in his texts strengthen “the euphonic secret” towards which the author guesses that language itself leads him. Writing, like horizon lines –oscillograms– is at once a pentagram and a vibrating chord.

The author wonders whether his writing is not a rejection “of the excessively communicational use of words, of the misuse that is often made of replacement and exchange, as if words could be copied out from one language to another totally and absolutely, without having anything quite their own.” By echoing this reflection we would like to draw attention to the difficulty entailed in rendering an essay such as Horizons and Waistlines in another language, well aware of both the value and the shortcomings of the art of translation. JosephineWatson