Dalí

21 Nov 2012 - 25 Mar 2013

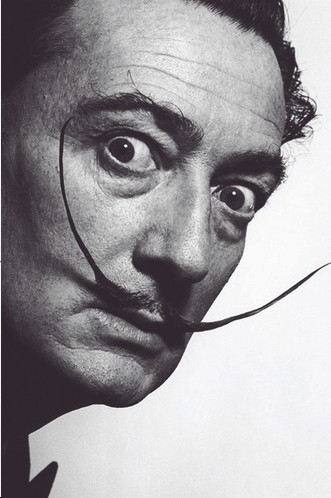

© halsman archive / magnum photos. droits d’image de salvador dalí réservés. fundació gala-salvador dalí ,figueres, 2012.

Photo: Philippe Halsman

Photo: Philippe Halsman

DALÍ

Curator : Mnam/Cci

21 November 2012 - 25 March 2013

HEAD CURATOR: JEAN-HUBERT MARTIN

CURATORS: MONTSE AGUER, DIRECTOR OF THE CENTRE FOR DALINIAN STUDIES; JEAN-MICHEL BOUHOURS, CURATOR, POMPIDOU NATIONAL MUSEUM OF MODERN ART; AND THIERRY DUFRÊNE, PROFESSOR OF THE HISTORY OF CONTEMPORARY ART (PARIS OUEST, NANTERRE LA DÉFENSE / INHA)

21 NOVEMBRE 2012

The Centre Pompidou pays tribute to one of the most complex and prolific great figures in 20th century art, Salvador Dalí, more than thirty years after the retrospective that the institution devoted to him in 1979-1980. Often criticised for his theatricality, his liking for money and his provocative stance on political issues, Dalí is both one of the most controversial artists and one of the most popular. This unprecedented exhibition sets out to throw light on the full power of his work and the part played in it by his personality and his strokes of genius as much as his outrageousness.

Among the masterpieces exhibited, visitors will rediscover some of the greatest iconic works, including the artist’s most famous picture, The Persistence of Memory, more commonly called Melting Watches. This exceptional loan from MoMA joins a selection of major works brought together for this retrospective thanks to a close collaboration with the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, and a joint contribution from the Fundació Dalí in Figueres and the Dali Museum in Saint Petersburg (Florida). With more than two hundred paintings, sculptures and drawings, to which are added films, extracts from broadcasts and photographs, the work of the pioneer of the “happening”, author of these ephemeral works, is also on show today. Michel Déon, who translated Dali’s writings, wanted the artist to be judged on his work. This is precisely the aim of this exhibition. Déon wanted him to abandon his “clowneries”: on the contrary, the exhibition shows that they were the acts of a shrewd artist “performer”, a pioneer, and full of humour. Dali liked to blend art and science, his famous paranoiac-critical method based on the delirium of performance claimed to treat all areas of creative activity as knowledge, in order to “dalinise” the world. This great media manipulator considered art a global act of communication. In all its facets, Dalí questioned the figure (persona) of the artist in the face of tradition and the world.

DALI SHOW,

BY JEAN-HUBERT MARTIN

Dalí’s fame is due as much to the originality of his painting as to his regular appearances in the media relaying his theatrical interventions. It is commonly thought that these representations of an unbridled imagination come under the heading of dreams. Yet Dali challenged this and made much of his paranoiac-critical method which goes well beyond hallucination.

“Paranoia makes use of the external world to validate the obsessive idea, with the disturbing characteristic of making the reality of this idea valid for others. The reality of the external world serves as an illustration of, proves, and is used to serve, the reality of our mind.” Hence the move from painting as a medium, to action, performance and happenings. Dali’s public appearances and ephemeral works have often been dismissed as provocations. Certainly, they take that form, but are always based on a point and on ideas which, to make them surprising, are no less consistent with them.

His media appearances ruled nothing out, simply being treated as a clown was enough for him to appear dressed up as an Auguste. His trips to the United States made him understand the importance of the media and the advantage that fame could give him. The advent of television was a godsend and he never missed an opportunity to appear on a talk show, at the risk of sometimes being disconcerted by the language and the unwritten rules, yet he was always able to rise above this and turn it to his own advantage. The idea of a purist conception of an art independent of commerce, money or showbusiness could not have been further from his own. Warhol, who often dined with him in New York, could have learned some lessons from him. For an entire generation, the advertising film for Lanvin chocolate made him as famous as his painting. His moustaches were the subject of endless comment. Having done an action painting in a few brushstrokes on television in order to criticise this type of painting, he repeated this virtuoso exercise and made a speciality of it. Since his life was nothing but theatre, he surrounded himself with women in various states of undress and bit part players to whom he assigned roles and postures in the staged scenarios of his own invention. The living pictures often involved the presence of the animals by which he was surrounded, like the famous ocelot (with filed teeth) or the anteater that he kept on a leash as he came out of the metro. In the 1950s and 1960s, a great many artists participated in his performances, which sometimes gave way to happenings, as in Granollers where dozens of young people sprayed themselves with paint in front of a large wall.

These multiple media activities and the constant creation of events in which Dali appeared in the starring role as – “Arteur” – made him the pioneer of performance art.

HARD SCIENCES AND MELTING WATCHES

BY THIERRY DUFRÊNE

On the subject of “melting watches” (The Persistence of Memory), the archives of MoMA in New York contain a few nuggets. Dalí himself did not manage to work out its full meaning. In “notes on the interpretation of the picture” written in 1931, he associates it with two very different types of knowledge: “Morphology – Gestalt la Residencia de los Estudiantes in the early 1920s”, is also mentioned in his “notes”: “The Persistence of Memory should be placed in the period of formation of Dali’s superego, very difficult still to specify chronologically”! While the “melting watches” offer a convincing image for one of the most complicated concepts of 20th century science: that of Einstein’s “space-time” continuum, Dali quite quickly confers on them the status of object-concept which is, “theory – mystery of the unduloids – geodesic lines”, in short, hard sciences on the one hand, “Psychoanalysis”, Freudianism and depth psychology on the other. His library, conserved at the Centre for Dalinian Studies in Figueres, has a wealth of scientific works. Dalí possessed the first edition of the Principes de morphologie générale (1927) [Principles of General Morphology] by Édouard Monod-Herzen, a specialist in colloids. But Dali’s early reading of Freud’s works, from the era when he was far from being his own brand, for him, on its own, symbolises modern science. Indeed, in 1934, in a letter to the poet Paul Eluard in which he talks about ”surrealism steeped in physics” and in his piece, “The surrealist and phenomenal mystery of the bedside table”, Dalí made reference to Einstein. In 1967, he confided to Louis Pauwels, author of Passions selon Dalí [Passions according to Dali]: “I said to Watson, during a lunch in New York: My picture, The Persistence of Memory, painted in 1931, is a prediction of DNA” : the same fluid, flexible and repetitive structure. Crick and Watson were the discoverers of the helix structure of DNA, the genetic code of heredity: Dalí had hoped to do a book with them. He was convinced that this “staircase of the structures of heredity” was none other than a “royal ladder” and that “nothing (was) more monarchal than a DNA molecule” ! The picture Galacidallahcideésoxyribonucléique (1963) used it as a basic structure. As for the atomic structure of matter, the inventor of the “nuclear mystique” had had an intuition about it while observing a “swarm of flies” at Boulou, not far from Perpignan station! Dali was intrigued by the way they maintained their configuration as a group without touching each other as they moved around: “I mentally drew a shape which I was to learn later was the diagram of the atom conceived by Niels Bohr”! Had people listened to Dali, without a moment’s hesitation the headquarters of the national centre for scientific research (CNRS) would have been located at Perpignan station. For the artist, not only was the glass roof the “model of the universe”, but it revealed to anyone who really wished to see that the “universe is limited, but only on one side”: “All that comes from infinity may make a loop and arrive at Perpignan station. I was collaborating with Einstein”.

MISTER DALI

BY JEAN-MICHEL BOUHOURS

When Dali wrote La Vie secrete [The Secret Life of Salvador Dali] in 1941, he described the years in his youth when, hiding away in the laundry room under the eaves of the family house, he had already adopted a posture that he never abandoned. He would perch himself on a seat high above the crowd, so as to longer be intimidated by the girls he met in the street who “embarrassed him”. This feeling of superiority hid a boundless shyness, which deprived Dali of the pleasures of everyday life: “I, Salvador, must remain in my tub with the shapeless and embittered chimeras that surround my rebarbative personality.” (p 87, La Vie secrète) Dali sought to attract the attention of his teachers at the San Fernando Academy in Madrid, by activating his exhibitionist tendencies: “Since they couldn’t teach me anything, I thought that I, I, was going to explain to them what a personality is”. He constructed it like an extraordinarily valuable asset: “I would not have wanted for anything in the world to exchange my personality with that of one of my contemporaries.” (p 174, La Vie secrète). Nonetheless, when Gala met Dali in the summer of 1930, she found him unpleasant in the first few moments, mainly because of this construction of a somewhat eccentric persona, beneath the appearance of a tango dancer with slicked down hair.

Dali dancing the Charleston; another photograph cut and pasted into a letter sent to his friend Federico Garcia Lorca, shows him cavorting around like a puppet waving his arms and legs, tie flying in the wind. Thirty years later, in 1958 to be precise, Pierre Argillet, the photographer and publisher, a friend of the surrealists, would film Dali dancing the Charleston in their garden. A few months later, the artist told the American talk show host Mike Wallace that his friends, surprised by his qualities as a dancer, compared him favourably to Charlie Chaplin. Dali went one step further, making it clear that since Chaplin was not a painter of genius, he was inevitably more important than Chaplin. This childish attitude sheds light on the whole of Dali’s strategy: to be famous, not as a painter, competing with the ever-present and dominant figure of Pablo Picasso, but more still: as a “super-painter”. Why not be a painter and an actor, like Buster Keaton who he and his companions at La Residencia de estudiantes in Madrid saw as both actor and a poet. Dali gave the journalist the perfect clarification of this attitude: “More important than my painting, more important than my clowning, more important than my showmanship, is MY PERSONALITY.”

And to create an identity for himself he had to invent “tricks”, as he himself was to write in La Vie secrète. This is brought about by creating a self-image, constructing a portrait for oneself to ensure a presence and “invent oneself in it” as the philosopher Jean- Luc Nancy later wrote (Le Regard du portrait. Paris, 2000, Galilée, p 31). Self-portrait with the neck of Raphael, painted around 1921, is probably one of the very first of Dali’s manifestations or masquerades, who was seeking mimicry with this portrait, a resemblance capable of triggering an associative mechanism of the paranoic type: “I liked to adopt the pose and melancholy gaze of Raphael in his self-portrait. I waited impatiently for the appearance of the first fluffy down that I could shave, while leaving a few favourites to grow. I had to make a masterpiece of my head, compose myself a face.” (ibidem, p. 40). The question of resemblance rekindled Dali’s propensity for twinning and double narcissism, and especially “Castor and Pollux”, the couple he formed with his dead half-brother, then with Galutschka, Federico Garcia Lorca and lastly with Gala. The principle of resemblance of two subjects, and later of two forms, is the trigger factor for an outrageous character. In Dali, comparison is not reason but reasoning outrageousness. The distinctive morphological feature invented with Self-portrait with the neck of Raphael, relies on the exhibitionism of a phallic neck, a first manifestation of the phallic head theme, before the “cranian” harps of the 1930s which would powerfully portray his terror of the sexual act and penetration.

So Dali initiated the narcissistic exhibition of his genius. Through autosuggestion, superstition or simply bravado, Dalinian excess deliberately operates by borrowing identity - at the pinnacle of his fame Salvador Dalí would borrow multiple personalities, particularly that of the Spanish painter Velázquez, a resemblance to whom he created with his famous moustache.

Curator : Mnam/Cci

21 November 2012 - 25 March 2013

HEAD CURATOR: JEAN-HUBERT MARTIN

CURATORS: MONTSE AGUER, DIRECTOR OF THE CENTRE FOR DALINIAN STUDIES; JEAN-MICHEL BOUHOURS, CURATOR, POMPIDOU NATIONAL MUSEUM OF MODERN ART; AND THIERRY DUFRÊNE, PROFESSOR OF THE HISTORY OF CONTEMPORARY ART (PARIS OUEST, NANTERRE LA DÉFENSE / INHA)

21 NOVEMBRE 2012

The Centre Pompidou pays tribute to one of the most complex and prolific great figures in 20th century art, Salvador Dalí, more than thirty years after the retrospective that the institution devoted to him in 1979-1980. Often criticised for his theatricality, his liking for money and his provocative stance on political issues, Dalí is both one of the most controversial artists and one of the most popular. This unprecedented exhibition sets out to throw light on the full power of his work and the part played in it by his personality and his strokes of genius as much as his outrageousness.

Among the masterpieces exhibited, visitors will rediscover some of the greatest iconic works, including the artist’s most famous picture, The Persistence of Memory, more commonly called Melting Watches. This exceptional loan from MoMA joins a selection of major works brought together for this retrospective thanks to a close collaboration with the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, and a joint contribution from the Fundació Dalí in Figueres and the Dali Museum in Saint Petersburg (Florida). With more than two hundred paintings, sculptures and drawings, to which are added films, extracts from broadcasts and photographs, the work of the pioneer of the “happening”, author of these ephemeral works, is also on show today. Michel Déon, who translated Dali’s writings, wanted the artist to be judged on his work. This is precisely the aim of this exhibition. Déon wanted him to abandon his “clowneries”: on the contrary, the exhibition shows that they were the acts of a shrewd artist “performer”, a pioneer, and full of humour. Dali liked to blend art and science, his famous paranoiac-critical method based on the delirium of performance claimed to treat all areas of creative activity as knowledge, in order to “dalinise” the world. This great media manipulator considered art a global act of communication. In all its facets, Dalí questioned the figure (persona) of the artist in the face of tradition and the world.

DALI SHOW,

BY JEAN-HUBERT MARTIN

Dalí’s fame is due as much to the originality of his painting as to his regular appearances in the media relaying his theatrical interventions. It is commonly thought that these representations of an unbridled imagination come under the heading of dreams. Yet Dali challenged this and made much of his paranoiac-critical method which goes well beyond hallucination.

“Paranoia makes use of the external world to validate the obsessive idea, with the disturbing characteristic of making the reality of this idea valid for others. The reality of the external world serves as an illustration of, proves, and is used to serve, the reality of our mind.” Hence the move from painting as a medium, to action, performance and happenings. Dali’s public appearances and ephemeral works have often been dismissed as provocations. Certainly, they take that form, but are always based on a point and on ideas which, to make them surprising, are no less consistent with them.

His media appearances ruled nothing out, simply being treated as a clown was enough for him to appear dressed up as an Auguste. His trips to the United States made him understand the importance of the media and the advantage that fame could give him. The advent of television was a godsend and he never missed an opportunity to appear on a talk show, at the risk of sometimes being disconcerted by the language and the unwritten rules, yet he was always able to rise above this and turn it to his own advantage. The idea of a purist conception of an art independent of commerce, money or showbusiness could not have been further from his own. Warhol, who often dined with him in New York, could have learned some lessons from him. For an entire generation, the advertising film for Lanvin chocolate made him as famous as his painting. His moustaches were the subject of endless comment. Having done an action painting in a few brushstrokes on television in order to criticise this type of painting, he repeated this virtuoso exercise and made a speciality of it. Since his life was nothing but theatre, he surrounded himself with women in various states of undress and bit part players to whom he assigned roles and postures in the staged scenarios of his own invention. The living pictures often involved the presence of the animals by which he was surrounded, like the famous ocelot (with filed teeth) or the anteater that he kept on a leash as he came out of the metro. In the 1950s and 1960s, a great many artists participated in his performances, which sometimes gave way to happenings, as in Granollers where dozens of young people sprayed themselves with paint in front of a large wall.

These multiple media activities and the constant creation of events in which Dali appeared in the starring role as – “Arteur” – made him the pioneer of performance art.

HARD SCIENCES AND MELTING WATCHES

BY THIERRY DUFRÊNE

On the subject of “melting watches” (The Persistence of Memory), the archives of MoMA in New York contain a few nuggets. Dalí himself did not manage to work out its full meaning. In “notes on the interpretation of the picture” written in 1931, he associates it with two very different types of knowledge: “Morphology – Gestalt la Residencia de los Estudiantes in the early 1920s”, is also mentioned in his “notes”: “The Persistence of Memory should be placed in the period of formation of Dali’s superego, very difficult still to specify chronologically”! While the “melting watches” offer a convincing image for one of the most complicated concepts of 20th century science: that of Einstein’s “space-time” continuum, Dali quite quickly confers on them the status of object-concept which is, “theory – mystery of the unduloids – geodesic lines”, in short, hard sciences on the one hand, “Psychoanalysis”, Freudianism and depth psychology on the other. His library, conserved at the Centre for Dalinian Studies in Figueres, has a wealth of scientific works. Dalí possessed the first edition of the Principes de morphologie générale (1927) [Principles of General Morphology] by Édouard Monod-Herzen, a specialist in colloids. But Dali’s early reading of Freud’s works, from the era when he was far from being his own brand, for him, on its own, symbolises modern science. Indeed, in 1934, in a letter to the poet Paul Eluard in which he talks about ”surrealism steeped in physics” and in his piece, “The surrealist and phenomenal mystery of the bedside table”, Dalí made reference to Einstein. In 1967, he confided to Louis Pauwels, author of Passions selon Dalí [Passions according to Dali]: “I said to Watson, during a lunch in New York: My picture, The Persistence of Memory, painted in 1931, is a prediction of DNA” : the same fluid, flexible and repetitive structure. Crick and Watson were the discoverers of the helix structure of DNA, the genetic code of heredity: Dalí had hoped to do a book with them. He was convinced that this “staircase of the structures of heredity” was none other than a “royal ladder” and that “nothing (was) more monarchal than a DNA molecule” ! The picture Galacidallahcideésoxyribonucléique (1963) used it as a basic structure. As for the atomic structure of matter, the inventor of the “nuclear mystique” had had an intuition about it while observing a “swarm of flies” at Boulou, not far from Perpignan station! Dali was intrigued by the way they maintained their configuration as a group without touching each other as they moved around: “I mentally drew a shape which I was to learn later was the diagram of the atom conceived by Niels Bohr”! Had people listened to Dali, without a moment’s hesitation the headquarters of the national centre for scientific research (CNRS) would have been located at Perpignan station. For the artist, not only was the glass roof the “model of the universe”, but it revealed to anyone who really wished to see that the “universe is limited, but only on one side”: “All that comes from infinity may make a loop and arrive at Perpignan station. I was collaborating with Einstein”.

MISTER DALI

BY JEAN-MICHEL BOUHOURS

When Dali wrote La Vie secrete [The Secret Life of Salvador Dali] in 1941, he described the years in his youth when, hiding away in the laundry room under the eaves of the family house, he had already adopted a posture that he never abandoned. He would perch himself on a seat high above the crowd, so as to longer be intimidated by the girls he met in the street who “embarrassed him”. This feeling of superiority hid a boundless shyness, which deprived Dali of the pleasures of everyday life: “I, Salvador, must remain in my tub with the shapeless and embittered chimeras that surround my rebarbative personality.” (p 87, La Vie secrète) Dali sought to attract the attention of his teachers at the San Fernando Academy in Madrid, by activating his exhibitionist tendencies: “Since they couldn’t teach me anything, I thought that I, I, was going to explain to them what a personality is”. He constructed it like an extraordinarily valuable asset: “I would not have wanted for anything in the world to exchange my personality with that of one of my contemporaries.” (p 174, La Vie secrète). Nonetheless, when Gala met Dali in the summer of 1930, she found him unpleasant in the first few moments, mainly because of this construction of a somewhat eccentric persona, beneath the appearance of a tango dancer with slicked down hair.

Dali dancing the Charleston; another photograph cut and pasted into a letter sent to his friend Federico Garcia Lorca, shows him cavorting around like a puppet waving his arms and legs, tie flying in the wind. Thirty years later, in 1958 to be precise, Pierre Argillet, the photographer and publisher, a friend of the surrealists, would film Dali dancing the Charleston in their garden. A few months later, the artist told the American talk show host Mike Wallace that his friends, surprised by his qualities as a dancer, compared him favourably to Charlie Chaplin. Dali went one step further, making it clear that since Chaplin was not a painter of genius, he was inevitably more important than Chaplin. This childish attitude sheds light on the whole of Dali’s strategy: to be famous, not as a painter, competing with the ever-present and dominant figure of Pablo Picasso, but more still: as a “super-painter”. Why not be a painter and an actor, like Buster Keaton who he and his companions at La Residencia de estudiantes in Madrid saw as both actor and a poet. Dali gave the journalist the perfect clarification of this attitude: “More important than my painting, more important than my clowning, more important than my showmanship, is MY PERSONALITY.”

And to create an identity for himself he had to invent “tricks”, as he himself was to write in La Vie secrète. This is brought about by creating a self-image, constructing a portrait for oneself to ensure a presence and “invent oneself in it” as the philosopher Jean- Luc Nancy later wrote (Le Regard du portrait. Paris, 2000, Galilée, p 31). Self-portrait with the neck of Raphael, painted around 1921, is probably one of the very first of Dali’s manifestations or masquerades, who was seeking mimicry with this portrait, a resemblance capable of triggering an associative mechanism of the paranoic type: “I liked to adopt the pose and melancholy gaze of Raphael in his self-portrait. I waited impatiently for the appearance of the first fluffy down that I could shave, while leaving a few favourites to grow. I had to make a masterpiece of my head, compose myself a face.” (ibidem, p. 40). The question of resemblance rekindled Dali’s propensity for twinning and double narcissism, and especially “Castor and Pollux”, the couple he formed with his dead half-brother, then with Galutschka, Federico Garcia Lorca and lastly with Gala. The principle of resemblance of two subjects, and later of two forms, is the trigger factor for an outrageous character. In Dali, comparison is not reason but reasoning outrageousness. The distinctive morphological feature invented with Self-portrait with the neck of Raphael, relies on the exhibitionism of a phallic neck, a first manifestation of the phallic head theme, before the “cranian” harps of the 1930s which would powerfully portray his terror of the sexual act and penetration.

So Dali initiated the narcissistic exhibition of his genius. Through autosuggestion, superstition or simply bravado, Dalinian excess deliberately operates by borrowing identity - at the pinnacle of his fame Salvador Dalí would borrow multiple personalities, particularly that of the Spanish painter Velázquez, a resemblance to whom he created with his famous moustache.