Uriel Orlow

Theatrum Botanicum

14 Apr - 17 Jun 2018

Uriel Orlow, Imbizo Ka Mafavuke, 2017 (video still)

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

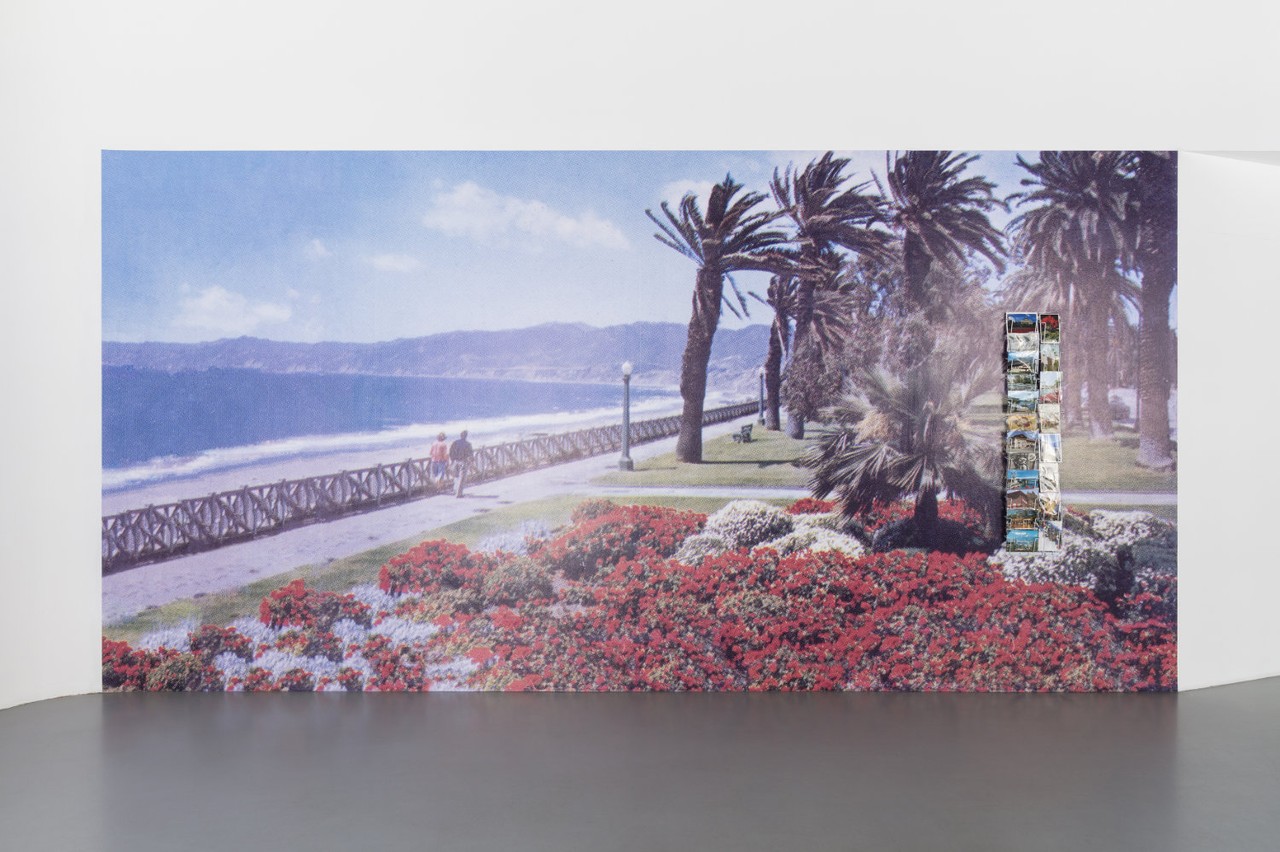

Uriel Orlow, Geraniums are Never Red, 2016

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

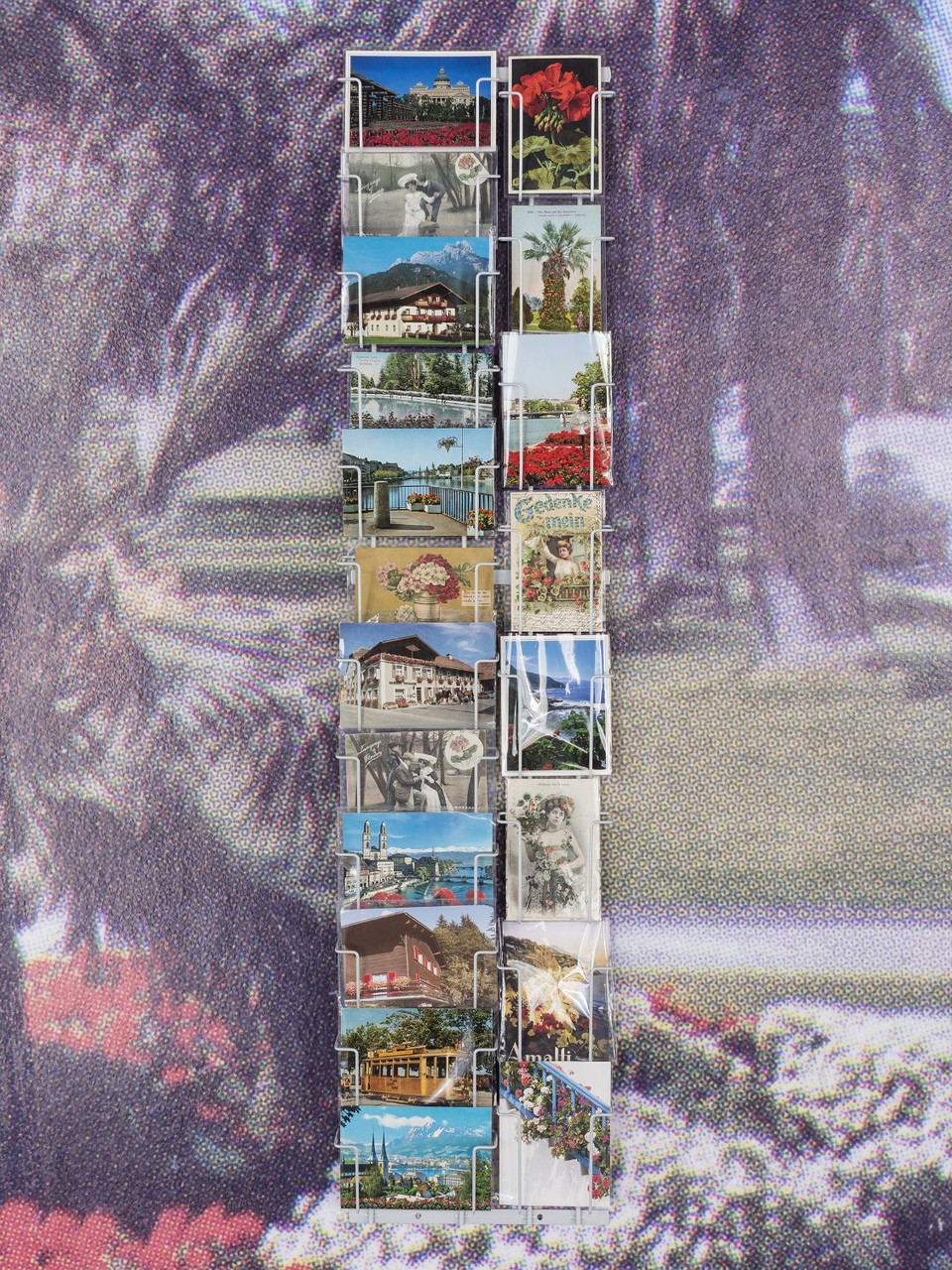

Uriel Orlow, Geraniums are Never Red, 2016 (detail)

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Uriel Orlow, Muthi, 2016-2017

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Uriel Orlow, exhibition view, The Crown Against Mafavuke, 2016; MAFAVUKE – The One Who Dies and Lives Again, Part 1 & Part 2 (detail), 2018; Echoes, 2018 (detail)

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Uriel Orlow, exhibition view, Imbizo Ka Mafavuke, 2017; MAFAVUKE – The One Who Dies and Lives Again, Part 1 (detail) & Part 2, 2018

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Uriel Orlow, exhibition view, Muthi, 2016-2017; The Crown Against Mafavuke, 2016

Courtesy: Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Courtesy: Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Uriel Orlow, exhibition view, MAFAVUKE – The One Who Dies and Lives Again, Part 1 & Part 2, 2018; Echoes, 2018 (detail); What Plants Were Called Before They Had a Name, since 2015 (ongoing) (detail); Grey, Green, Gold, 2015-2017 (detail)

Courtesy: Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Courtesy: Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Uriel Orlow, exhibition view, What Plants Were Called Before They Had a Name, since 2015 (ongoing); Echoes, 2018

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Uriel Orlow, Grey, Green, Gold, 2015-2017 (detail)

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

Courtesy: the artist, La Veronica, Modica, and Mor Charpentier, Paris

Photo: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier

In his research-based and process-oriented practice Uriel Orlow (born in Zurich, lives and works in London, Lisbon and Zurich) is concerned with blind spots in the representation of history and ensuing questions of restitution, including repatriating memory to the present. At Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen Orlow presents his large-scale body of work Theatrum Botanicum (2015–2017) which considers the botanical world as a stage for politics. Working from the dual vantage points of South Africa and Europe the project shows plants as witnesses and actors in history, as dynamic agents linking nature and humans, tradition and modernity — across various geographies, histories and knowledge systems. Films, sound works, photographs and installations highlight ‘botanical nationalism’ and other legacies of colonialism, plant migration, bio-piracy, flower diplomacy under apartheid, the role of classification and naming of plants as well as the garden planted by Mandela and his fellow inmates in Robben Island prison.

The centrepiece of the exhibition is a video trilogy which investigates the ideological and commercial confrontation of two different yet interwinging medicinal traditions and their use of plants (The Crown Against Mafavuke), considers questions around indigenous copyright protection (Imbizo Ka Mafavuke (Mafavuke’s Tribunal)) and documents the continuing presence of herbal medicine in the postcolonial context (Muthi).

The surround-sound installation What Plants Were Called Before They Had a Name for example can be seen against the background of the expeditions that preceded and accompanied European colonialism in South Africa (and elsewhere), that aimed at charting the territory and classifying its natural resources, in turn paving the way for occupation and exploitation. The supposed discovery and subsequent naming and cataloguing of plants disregarded and ultimately obliterated existing indigenous names and botanical knowledge as the Linnean system of classification with its particular European rationality was imposed. What Plants Were Called Before They Had a Name functions as an oral plant dictionary of indigenous South African languages such as Khoi, SePedi, SeSotho, Swazi, Tswana, Tsonga, Xhosa and Zulu.

Orlow used film material found in the basement of the library of the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden in Cape Town as the starting point for his video work The Fairest Heritage. The films were commissioned in 1963 for the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the garden, to document its history but also the jubilee celebrations with their ‘national’ dances, pantomimes of colonial conquest and visiting international botanists; the only Africans in the films are workers. Considered passive and neutral, flowers were excluded from the boycott for a long time and ‘botanical nationalism’ and flower diplomacy flourished unchecked in South Africa and abroad. For The Fairest Heritage Orlow worked with an actor who puts herself and her body in these loaded images, inhabiting and confronting the found film material, and thus contesting history and the archive itself.

«Theatrum Botanicum» not only profoundly engages with colonialism and recent historiography but also offers the opportunity to delve deeply into Uriel Orlow’s way of working.

Uriel Orlow (*1973 in Zurich) lives and works in London, Lisbon and Zurich. He studied at Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design London, the Slade School of Art and the University of Geneva, completing a PhD in Fine Art in 2002. Solo exhibitions (selection): PAV – Parco Arte Vivente, Turin/IT (2017); Parc Saint Léger – Centre d’Art Contemporain, Pougues-les-Eaux/FR (2017); The Showroom, London/UK (2016); Castello di Rivoli, Turin/IT (2015); John Hansard Gallery, Southampton/UK (2015); Depo, Istanbul/TR (2015); Kunsthaus Pasquart, Biel/CH (2012). Orlow’s works have been exhibited internationally in museums and galleries, amongst others in London/UK (Tate Modern, Tate Britain, Whitechapel Gallery, ICA and Gasworks), Paris/FR (Palais de Tokyo, Fondation Ricard, Maison Populaire, Bétonsalon), Zurich/CH (Kunsthaus, Les Complices, Helmhaus and Shedhalle) as well as Geneva/CH (Centre d’Art Contemporain and Centre de la Photographie). Orlow’s work was further presented at major survey exhibitions including: 7th Moscow Biennal, Moskow/RU (2017), Sharjah Biennale 13, Sharjah/UAE (2017), Manifesta 9, Genk/BE (2012); 54th Biennale di Venezia, Venice/IT (2011). Orlow’s films have been screened at Oberhausen Short Film Festival, Oberhausen/DE, Locarno Festival, Locarno/CH, Videoex, Zurich/CH, Centre Pompidou, Paris/FR; BFI London Film Festival, London/UK; Kino der Kunst, Munich/DE; Visions du Réel, Nyon/FR as well as the Biennale of the Moving Image, Geneva/CH.

The centrepiece of the exhibition is a video trilogy which investigates the ideological and commercial confrontation of two different yet interwinging medicinal traditions and their use of plants (The Crown Against Mafavuke), considers questions around indigenous copyright protection (Imbizo Ka Mafavuke (Mafavuke’s Tribunal)) and documents the continuing presence of herbal medicine in the postcolonial context (Muthi).

The surround-sound installation What Plants Were Called Before They Had a Name for example can be seen against the background of the expeditions that preceded and accompanied European colonialism in South Africa (and elsewhere), that aimed at charting the territory and classifying its natural resources, in turn paving the way for occupation and exploitation. The supposed discovery and subsequent naming and cataloguing of plants disregarded and ultimately obliterated existing indigenous names and botanical knowledge as the Linnean system of classification with its particular European rationality was imposed. What Plants Were Called Before They Had a Name functions as an oral plant dictionary of indigenous South African languages such as Khoi, SePedi, SeSotho, Swazi, Tswana, Tsonga, Xhosa and Zulu.

Orlow used film material found in the basement of the library of the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden in Cape Town as the starting point for his video work The Fairest Heritage. The films were commissioned in 1963 for the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the garden, to document its history but also the jubilee celebrations with their ‘national’ dances, pantomimes of colonial conquest and visiting international botanists; the only Africans in the films are workers. Considered passive and neutral, flowers were excluded from the boycott for a long time and ‘botanical nationalism’ and flower diplomacy flourished unchecked in South Africa and abroad. For The Fairest Heritage Orlow worked with an actor who puts herself and her body in these loaded images, inhabiting and confronting the found film material, and thus contesting history and the archive itself.

«Theatrum Botanicum» not only profoundly engages with colonialism and recent historiography but also offers the opportunity to delve deeply into Uriel Orlow’s way of working.

Uriel Orlow (*1973 in Zurich) lives and works in London, Lisbon and Zurich. He studied at Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design London, the Slade School of Art and the University of Geneva, completing a PhD in Fine Art in 2002. Solo exhibitions (selection): PAV – Parco Arte Vivente, Turin/IT (2017); Parc Saint Léger – Centre d’Art Contemporain, Pougues-les-Eaux/FR (2017); The Showroom, London/UK (2016); Castello di Rivoli, Turin/IT (2015); John Hansard Gallery, Southampton/UK (2015); Depo, Istanbul/TR (2015); Kunsthaus Pasquart, Biel/CH (2012). Orlow’s works have been exhibited internationally in museums and galleries, amongst others in London/UK (Tate Modern, Tate Britain, Whitechapel Gallery, ICA and Gasworks), Paris/FR (Palais de Tokyo, Fondation Ricard, Maison Populaire, Bétonsalon), Zurich/CH (Kunsthaus, Les Complices, Helmhaus and Shedhalle) as well as Geneva/CH (Centre d’Art Contemporain and Centre de la Photographie). Orlow’s work was further presented at major survey exhibitions including: 7th Moscow Biennal, Moskow/RU (2017), Sharjah Biennale 13, Sharjah/UAE (2017), Manifesta 9, Genk/BE (2012); 54th Biennale di Venezia, Venice/IT (2011). Orlow’s films have been screened at Oberhausen Short Film Festival, Oberhausen/DE, Locarno Festival, Locarno/CH, Videoex, Zurich/CH, Centre Pompidou, Paris/FR; BFI London Film Festival, London/UK; Kino der Kunst, Munich/DE; Visions du Réel, Nyon/FR as well as the Biennale of the Moving Image, Geneva/CH.