Gouge: The Modern Woodcut 1870 to Now

09 Nov 2008 - 08 Feb 2009

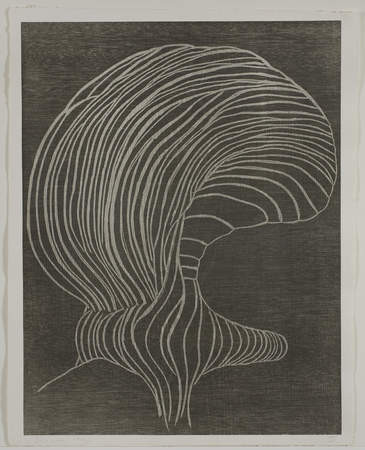

© Terry Winters

Furrows IV (detail), 1989

Printed by Francois Lafranca, published by Peter Blum Editions. 25-1/2 x 19-5/8 inches (image); 27 x 21-3/8 inches (sheet). Collection UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Hammer Museum. Purchased with funds provided by The Buddy Taub Foundation, Jill and Dennis Roach, Directors. Photo by Brian Forrest.

Furrows IV (detail), 1989

Printed by Francois Lafranca, published by Peter Blum Editions. 25-1/2 x 19-5/8 inches (image); 27 x 21-3/8 inches (sheet). Collection UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Hammer Museum. Purchased with funds provided by The Buddy Taub Foundation, Jill and Dennis Roach, Directors. Photo by Brian Forrest.

GOUGE: THE MODERN WOODCUT 1870 TO NOW

November 9 - February 8, 2009

Gouge: The Modern Woodcut 1870 to Now examines the woodcut in terms of its diverse forms and uses in the modern era. A thematic survey, it invites parallels between the medium in countries as diverse and geographically distant Mexico, France and Korea. Woodblock printing is, in fact, one of the most common artistic practices throughout the world. Although the motivations of each artist and the circumstances in which the woodcuts were made may differ greatly, the visual character of the gouge cuts is a defining thread among the selected works in this exhibition.

In its most basic form, the making of a woodcut requires just a block of wood, a cutting tool known as a gouge, some ink, and a sheet of paper. The birth of the woodcut can be traced back to the eighth century when Buddhist monks in Japan and China developed this basic printing practice to reproduce devotional texts. It did not establish itself in Europe until the beginning of the fifteenth century, reaching a technical and artistic apogee as a fine art medium in the hands of German master Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). Although the medium evolved thereafter, especially with the introduction of color to the chiaroscuro woodcut, it fell out of favor towards the end of the Renaissance. While the woodcut continued to be a common source for the dissemination of biblical and folk scenes, intaglio printing techniques (such as etching and engraving) were considered to be more sophisticated means of aesthetic communication. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the woodcut served primarily to illustrate street banners and broadsides or as reproductions in popular journals and calendars. It was partly this popular aspect of woodcuts, together with their organic quality and an easy accessibility to the natural materials, which lured artists back to the technique towards the end of the nineteenth century. Paul Gauguin and his contemporaries in France rediscovered the pure, untainted character of the woodcut and set the stage for a host of artists who experimented with the medium thereafter. The woodcut’s archaic yet versatile qualities nourished its evolution throughout the twentieth century, and the technique continues to take new directions within the contemporary studio.

November 9 - February 8, 2009

Gouge: The Modern Woodcut 1870 to Now examines the woodcut in terms of its diverse forms and uses in the modern era. A thematic survey, it invites parallels between the medium in countries as diverse and geographically distant Mexico, France and Korea. Woodblock printing is, in fact, one of the most common artistic practices throughout the world. Although the motivations of each artist and the circumstances in which the woodcuts were made may differ greatly, the visual character of the gouge cuts is a defining thread among the selected works in this exhibition.

In its most basic form, the making of a woodcut requires just a block of wood, a cutting tool known as a gouge, some ink, and a sheet of paper. The birth of the woodcut can be traced back to the eighth century when Buddhist monks in Japan and China developed this basic printing practice to reproduce devotional texts. It did not establish itself in Europe until the beginning of the fifteenth century, reaching a technical and artistic apogee as a fine art medium in the hands of German master Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). Although the medium evolved thereafter, especially with the introduction of color to the chiaroscuro woodcut, it fell out of favor towards the end of the Renaissance. While the woodcut continued to be a common source for the dissemination of biblical and folk scenes, intaglio printing techniques (such as etching and engraving) were considered to be more sophisticated means of aesthetic communication. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the woodcut served primarily to illustrate street banners and broadsides or as reproductions in popular journals and calendars. It was partly this popular aspect of woodcuts, together with their organic quality and an easy accessibility to the natural materials, which lured artists back to the technique towards the end of the nineteenth century. Paul Gauguin and his contemporaries in France rediscovered the pure, untainted character of the woodcut and set the stage for a host of artists who experimented with the medium thereafter. The woodcut’s archaic yet versatile qualities nourished its evolution throughout the twentieth century, and the technique continues to take new directions within the contemporary studio.