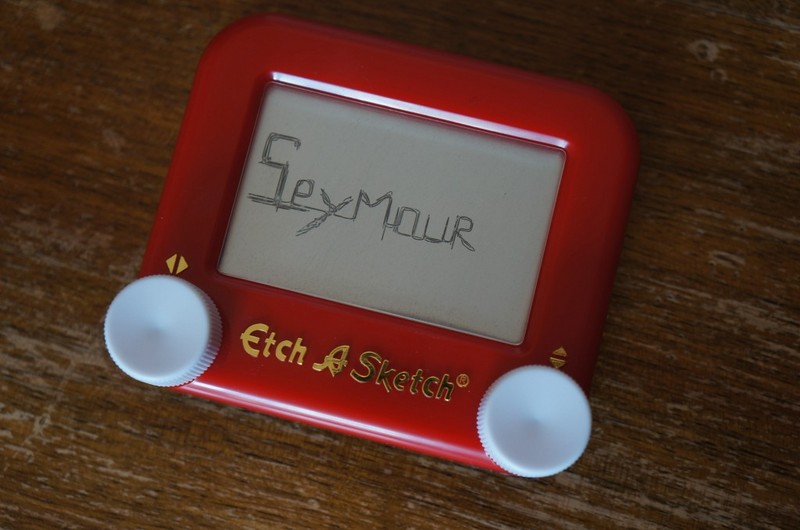

Seymour

21 Jun - 19 Oct 2014

SEYMOUR

21 June - 19 October 2014

With : Erica Baum, Lenka Clayton, Julien Crépieux, Moyra Davey, Joseph Grigely, Chitti Kasemkitvatana, Gareth Long, Benoît Maire, Benoît-Marie Moriceau, Antoinette Ohannessian, Bruno Persat, William Wegman and the participation of Holden.

Please accept from me this unpretentious bouquet of very early-blooming parentheses : (((()))).

J.D. Salinger, Seymour : An Introduction, 1959

Seymour is the eldest son of the Glass family. His six brothers and sisters are called Buddy, Boo Boo, Walt, Waker, Zooey and Franny, and his parents are Bessie and Les. Conceived by writer JD Salinger (1919-2010), the history of the family is told in eight short stories, most of them published in The New Yorker magazine between 1948 and 1965. Seymour is the central character in the saga yet only appears indirectly, in a fragmented and non-chronological way, through letters and stories told by his brothers and sisters. We already learn of his suicide at the age of 31, whilst on honeymoon, in the first of the series of short stories, A Perfect Day for Bananafish, while the last story published by Salinger during his lifetime, in 1965, is a long letter written by Seymour, then aged seven.

A “blue-striped unicorn, double-lensed burning glass, consultant genius, portable conscience, supercargo” for his brothers and sisters and a “mystical”, “unbalanced ” or “schizoid personality” according to others, Seymour seems constantly out of kilter with his environment and his times. “Paranoid in reverse”, claiming to be too happy to attend his own wedding, his character “lends itself to no legitimate sort of narrative compactness.” He nevertheless embodies the romantic anti-hero, in turn whimsical and desperate, whose quest for happiness, grace and spirituality cannot be accomplished in the superficial world which surrounds him. Through Seymour and members of the Glass family, Salinger unaffectedly evokes adolescence and its disillusionment faced with the loss of childhood innocence. Beyond a certain uneasiness, he also deals with an absolute need and an existential quest to confront the rise of a consumerist lifestyle in post-war New York. His personal interest in Zen Buddhism was also reflected in the character of Seymour, a follower of Eastern mysticism and Chinese and Japanese poetry.

Devised with the artist Bruno Persat, the group exhibition Seymour echoes this ambiguous character (with “a Heinzlike variety of personal characteristics”) through works which evoke some of the themes and narrative devices that appear in the saga of the Glass family including the enigma of happiness and melancholy, spleen and ideal, poetry and play, address and correspondence and the desperate enchantment of daily life.

Sipping a Tom Collins, we can expect to find in this exhibition the memory of a Buddhist retreat in the mountains of northern Thailand (Chitti Kasemkitvatana), dogs leading a police investigation between two games of tennis (William Wegman), fragmented images of a correspondence from the past (Moyra Davey), an alphabetical shopping receipt (Lenka Clayton), bamboo, 500mm puddles of water to be thrown into a river (Antoinette Ohannessian) poems found on library cards (Erica Baum), chance and knowledge brought together on a single canvas (Benoît Maire), excerpts from daily conversations glued to the walls (Joseph Grigely), a mathematical Zen garden (Bruno Persat), a domesticated sunset (Benoît-Marie Moriceau), 19th century clouds crystallized in salt (Julien Crépieux), a metaphysical geometric soundtrack (Holden), a portrait in unstable lines of one of Seymour’s brothers (Gareth Long).

21 June - 19 October 2014

With : Erica Baum, Lenka Clayton, Julien Crépieux, Moyra Davey, Joseph Grigely, Chitti Kasemkitvatana, Gareth Long, Benoît Maire, Benoît-Marie Moriceau, Antoinette Ohannessian, Bruno Persat, William Wegman and the participation of Holden.

Please accept from me this unpretentious bouquet of very early-blooming parentheses : (((()))).

J.D. Salinger, Seymour : An Introduction, 1959

Seymour is the eldest son of the Glass family. His six brothers and sisters are called Buddy, Boo Boo, Walt, Waker, Zooey and Franny, and his parents are Bessie and Les. Conceived by writer JD Salinger (1919-2010), the history of the family is told in eight short stories, most of them published in The New Yorker magazine between 1948 and 1965. Seymour is the central character in the saga yet only appears indirectly, in a fragmented and non-chronological way, through letters and stories told by his brothers and sisters. We already learn of his suicide at the age of 31, whilst on honeymoon, in the first of the series of short stories, A Perfect Day for Bananafish, while the last story published by Salinger during his lifetime, in 1965, is a long letter written by Seymour, then aged seven.

A “blue-striped unicorn, double-lensed burning glass, consultant genius, portable conscience, supercargo” for his brothers and sisters and a “mystical”, “unbalanced ” or “schizoid personality” according to others, Seymour seems constantly out of kilter with his environment and his times. “Paranoid in reverse”, claiming to be too happy to attend his own wedding, his character “lends itself to no legitimate sort of narrative compactness.” He nevertheless embodies the romantic anti-hero, in turn whimsical and desperate, whose quest for happiness, grace and spirituality cannot be accomplished in the superficial world which surrounds him. Through Seymour and members of the Glass family, Salinger unaffectedly evokes adolescence and its disillusionment faced with the loss of childhood innocence. Beyond a certain uneasiness, he also deals with an absolute need and an existential quest to confront the rise of a consumerist lifestyle in post-war New York. His personal interest in Zen Buddhism was also reflected in the character of Seymour, a follower of Eastern mysticism and Chinese and Japanese poetry.

Devised with the artist Bruno Persat, the group exhibition Seymour echoes this ambiguous character (with “a Heinzlike variety of personal characteristics”) through works which evoke some of the themes and narrative devices that appear in the saga of the Glass family including the enigma of happiness and melancholy, spleen and ideal, poetry and play, address and correspondence and the desperate enchantment of daily life.

Sipping a Tom Collins, we can expect to find in this exhibition the memory of a Buddhist retreat in the mountains of northern Thailand (Chitti Kasemkitvatana), dogs leading a police investigation between two games of tennis (William Wegman), fragmented images of a correspondence from the past (Moyra Davey), an alphabetical shopping receipt (Lenka Clayton), bamboo, 500mm puddles of water to be thrown into a river (Antoinette Ohannessian) poems found on library cards (Erica Baum), chance and knowledge brought together on a single canvas (Benoît Maire), excerpts from daily conversations glued to the walls (Joseph Grigely), a mathematical Zen garden (Bruno Persat), a domesticated sunset (Benoît-Marie Moriceau), 19th century clouds crystallized in salt (Julien Crépieux), a metaphysical geometric soundtrack (Holden), a portrait in unstable lines of one of Seymour’s brothers (Gareth Long).